This piece is in response to the interview between Dwarkesh Patel & Richard Sutton. In it, I challenge Sutton’s claim that LLMs cannot form world models and therefore cannot be goal-seeking agents, but acknowledge the significance of a deep training set for eliciting LLM capabilities.

Language as a representational medium for world modelling

Sutton claims there is “no ground truth in [LLMs]” and implies that LLMs do not get to observe the outcomes of the real world. My understanding is that Sutton is suggesting that the natural language LLMs are trained on is unable to represent the real world. I reject this notion; I believe language is a representational medium no less valid than other traditional representational mediums, such as our senses.

Ultimately, any representational medium is just translation and compression of the underlying world being modelled. Information about the world is encoded into a latent representation. Language plays this exact role, it translates and compresses information about any domain.

The role of these representational mediums is to provide a useful representation. The representation must allow the associated intelligence to gain understanding, so that it can make good predictions and decisions about the underlying world. So long as the necessary information can be conveyed, the representational medium is valid.

To illustrate this, consider how humans model the spatial world, typically using our senses. Whilst these representations feel incredibly vivid and immediate to us, we do not have access to the object-level material world, we only get a representation. The electromagnetic waves that hit our eyes are only an imprint of the spatial world. Our vision is supplemented by other sensory representations, but even all this together is incredibly lossy. We lose huge amounts of information about the underlying spatial world in our sensory representations. Additionally, we lose even more information when our brains compress/organise our sensory data into an interpretable first person experience. Despite all this informational loss, it seems obvious to suggest that humans are able to form a model of the spatial world.

Language is also capable of describing the spatial world. Compared to vision, natural language doesn’t represent all details as eloquently, but it also has the capacity to represent details of the world that vision cannot. I could say “the bathroom is down the hallway, first door on the left”. This phrase may not paint the vivid colours & contours that my vision does, but it does create a 3D mapping that I couldn’t get from a single visual snapshot.

Language can in theory translate anything that can be represented by other mediums. In the limit, you could just use language to map out any set of information in 1s and 0s (bits), even though this is almost certainly not the most effective method of compression. In theory, any representational medium should be suitable for representing any world, so long as it could represent information in binary terms.

The importance of datasets & the danger for LLMs

It is one thing to point out that language is suitable for world modelling, but to evaluate how capable LLMs can be, we must also consider what information is actually contained in the training set. Imagine a training set containing billions of words just stating the scores and team names for every basketball match ever played. A model trained on this may get quite good at predicting basketball outcomes, but obviously it would have almost no capacity to model other parts of the world, there just isn’t enough relevant information to model.

With such large datasets, it is hard to fully assess and even articulate what inferrable information is actually present. Most of the problem spaces that LLMs struggle with are domains where language does a poor job at giving an efficient and informationally dense representation. An LLM will not do anywhere near as good of a job at describing the exact contours of some object, when compared to an image of that object. We may be able to describe contours with language that compresses the ideas, but the compression is too lossy and we lose information when we decompress.

Do LLMs make predictions about the world?

Sutton centres much of his argument around the claim that LLMs do not make predictions about the world. “There’s no ground truth in large language models because you don’t have a prediction about what will happen next.” I reject this claim.

Current leading LLMs, during inference, are clearly making predictions about what will happen next in the world. Even if an LLMs output is in the form of a next token prediction, LLMs are clearly still producing an internal representation of what comes next. World modelling is occurring somewhere in the neural network.

To predict what will happen next is to make a prediction about how S(t) will transition S(t+1), given action a(t). Consider the interaction below:

User:

‘In my kitchen, I have a chair, on top of the chair is a bowl, inside the bowl is a cup, inside the cup is a coin. I take the chair into my bedroom, then I take the bowl off the chair and turn it upside-down. I take the bowl and put it back on the chair. I take the chair to my bathroom and put it down. Where is the coin?’

GPT 5 Thinking:

‘In the bedroom—still inside the cup (which fell out when you flipped the bowl), on the floor.’

To answer this question accurately and produce a sensible output sequence of tokens, the LLM had to model the physical world, understand its dynamics and be able to internally form a prediction of what would happen next. It is clearly able to map S(t) to S(t+1) given a(t).

Can LLMs form the basis of an agent?

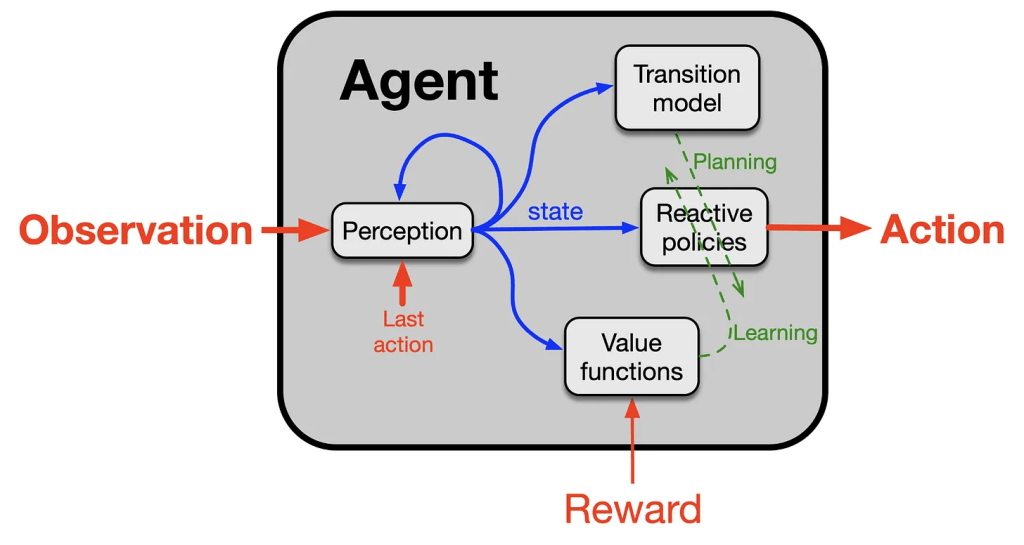

In the interview, Sutton outlines a ‘base common model of the agent’. He describes 4 necessary components of an agent: policy, value function, perception & transition model. Sutton’s claim is that LLMs do not have a transition model, a model for the transition from one state to the next based on an agent’s action. He describes the transition model as: “Your belief that if you do this, what will happen? What will be the consequences of what you do? Your physics of the world. But it’s not just physics, it’s also abstract models”. He claims that because LLMs do not have a transition model, they cannot form the basis of agents.

I reject this claim; I believe LLMs do in fact have transition models and can form the basis of agents. As described in the previous section, LLMs clearly have the capacity to make predictions about the world. The question is whether the capacity to make predictions about the world constitutes a transition model.

A subtle distinction here is that LLMs do not necessarily model the world in a manner through which they see themselves as part of the world they are modelling. When they model state-action pairs, they are not modelling their own actions, rather they model the actions of other agents in the world they are modelling.

It is worth noting though that if an LLM is given the context of a physical agent and told to output actions on its behalf (i.e. told you have the capacity to take this set of actions, have the state described to them and then actually have the actions taken on its behalf) they would probably be able to be quite competent in this domain, so at the least they aren’t totally incapable of adhering to this base common model of the agent.

Still, this distinction points to a critical difference between general purpose LLMs and agents; when LLMs are instructed to solve a problem, they are not fully optimised to output the reward-maximising solution, rather they produce the most likely next token. This often correlates greatly with the reward-maximising solution, but these are distinct problems and is a source of limitations in the LLMs capacity to act as an agent.

However, if we ask whether LLMs can form the basis of agents, then it seems that this problem should be something that can be bypassed in post-training. As alluded to by Dwarkesh, during the interview, we should be able to take an LLM with a pretrained general world model and then start updating its weights to optimise for rewards on actions. If we accept that language is a valid medium to represent the world, it should be totally tractable to use the LLM as the foundational piece in the base common model of the agent, described by Sutton.

It should be noted that this does seem to conflict with the Sutton’s Bitter Lesson framework, the idea that methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective. Yet when it comes to the necessity for a method to scale absolutely with compute, Andrej Karpathy frames it nicely: ‘And I still think the bitter lesson is correct, but I see it more as something platonic to pursue, not necessarily to reach, in our real world and practically speaking.’ The Bitter Lesson is something to aim for directionally, but not necessarily something that must be obtained in the purest sense.

Leave a comment